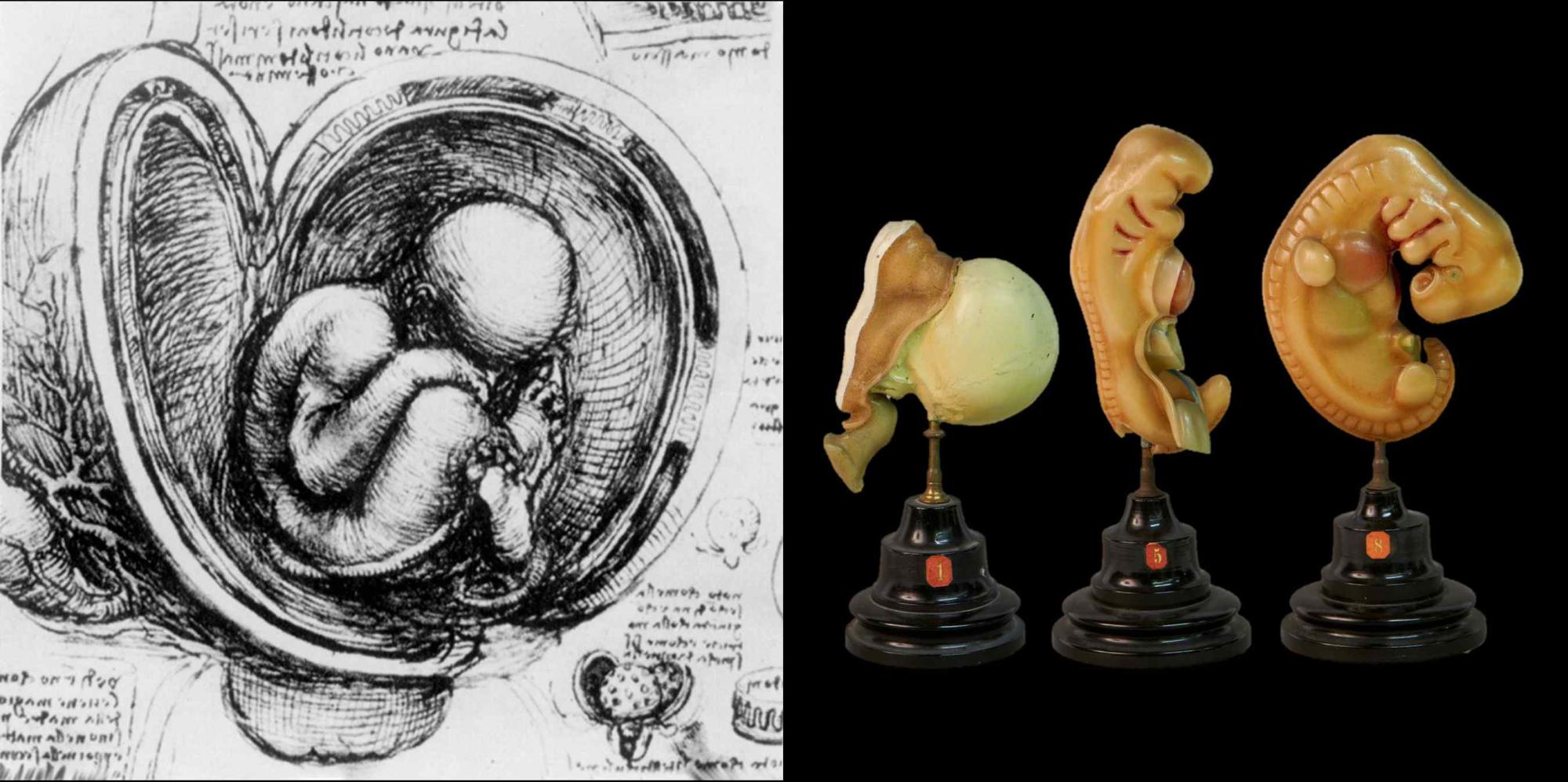

Leonardo da Vinci, in the late 1400s and early 1500s, was among the first to document that embryos change in weight, size, and shape over time. His famous drawing of a human fetus inside a dissected uterus, although later identified as the uterus of an ungulate, marked a significant milestone in visualizing embryonic development (Fig. 1A).

With the development of microscopy, enabling the visualization of individual cells, research on developmental anatomy accelerated. One of the first major collections of human embryonic and fetal specimens was the Carnegie collection, established by Franklin P. Mall in the late 1800s. The Carnegie stages, widely used in human embryology, were defined based on the characteristics of embryos from this collection.

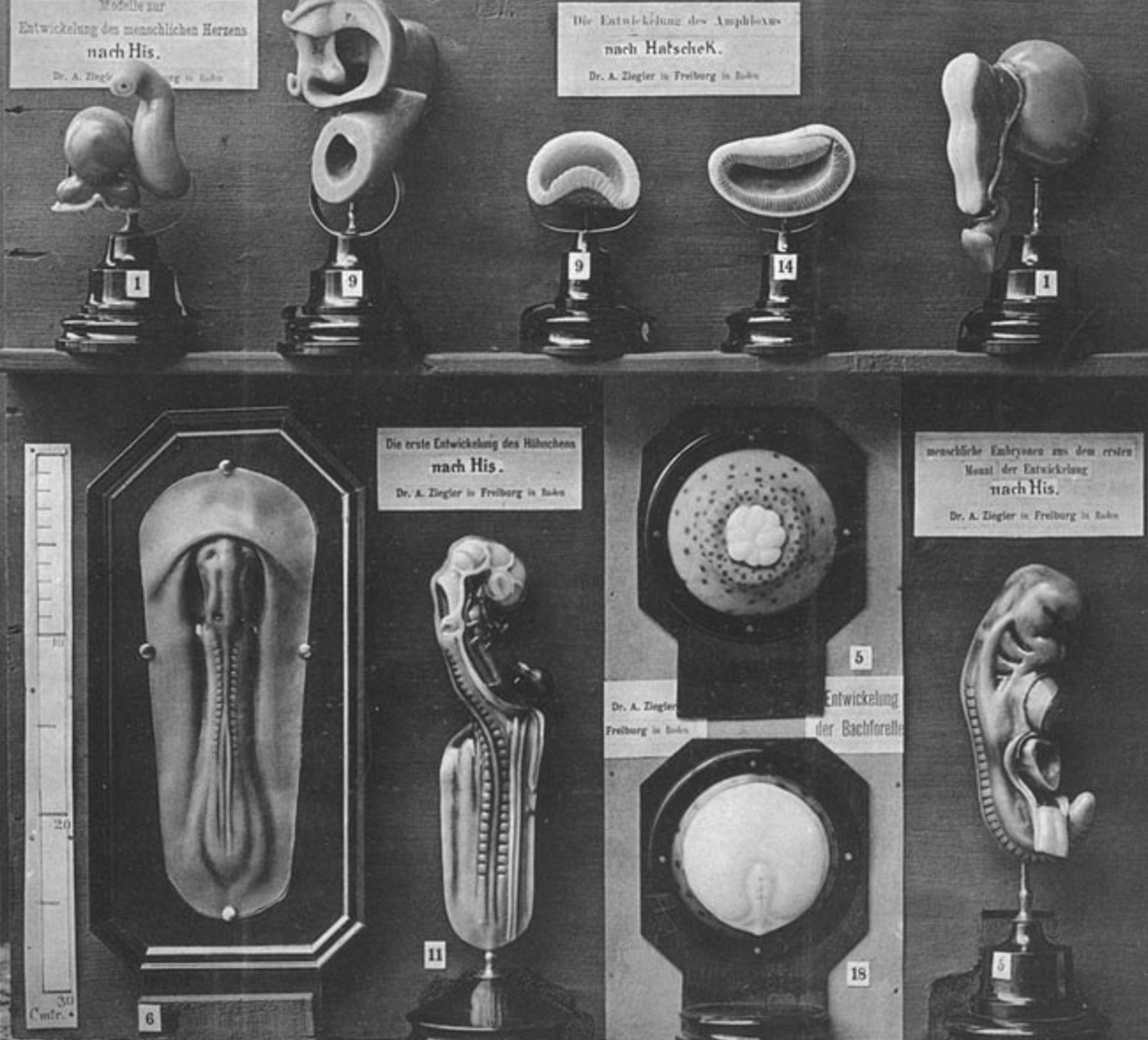

Early illustrations and wall charts of embryos, while useful, lacked a three-dimensional perspective. Adolf Ziegler advanced this field by creating three-dimensional wax models from two-dimensional illustrations (Fig. 1B and 2). Later, Gustav Born’s technique of stacking wax sheets, cut and projected from microscopic sections, allowed for accurate 3D renditions of embryos, much like primitive 3D printing.

Osborne O. Heard used histological sections from the Carnegie collection to create detailed 3D reconstructions (Fig. 3), leading to famous drawings by artists like James F. Didusch. These wax models provided crucial insights into early human development, despite being labor-intensive and fragile.